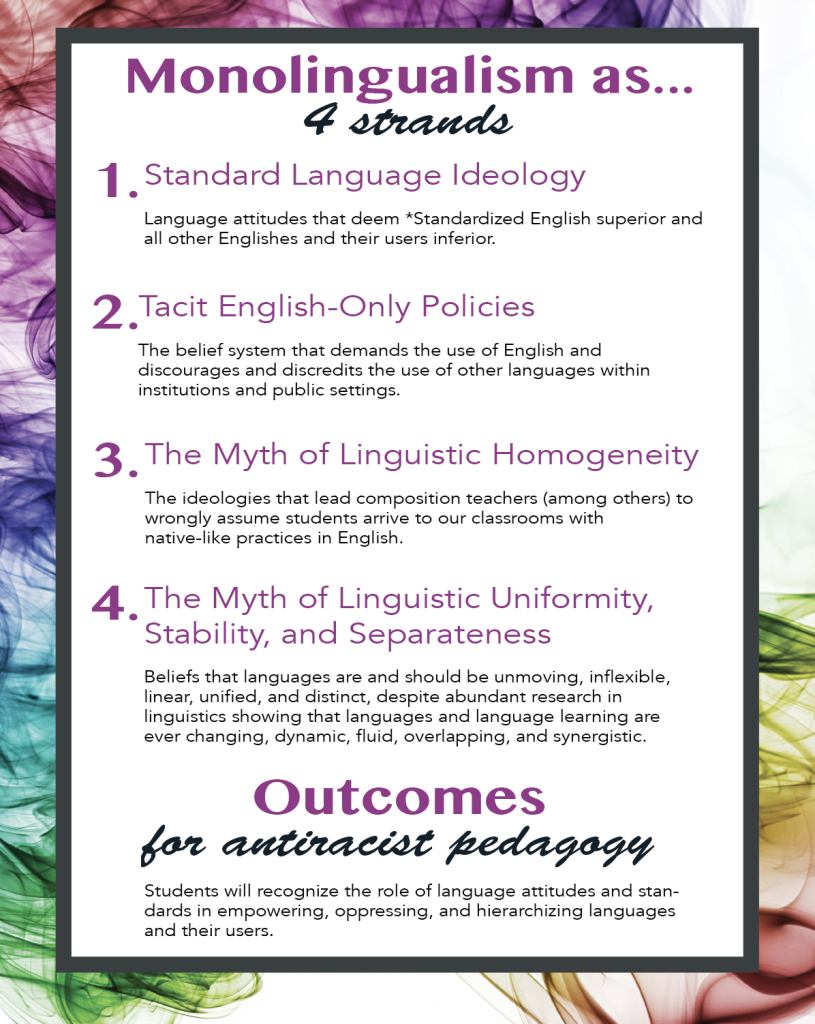

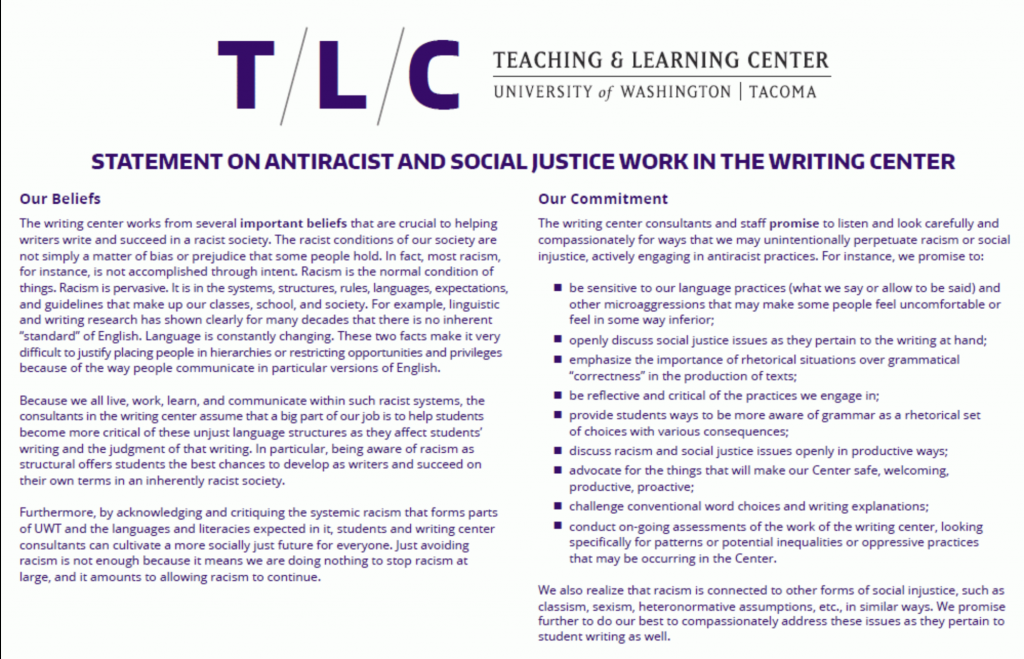

Teaching writing is a wonderful opportunity to engage students in discussions and practices of social justice. This is because writing – particularly as it is assessed and linked to social opportunity in higher education – is deeply entangled in forms of social injustice. This is, in large part, because language standardization, grammar, and academic writing standards, as Asao Inoue notes, can quickly be wielded in classrooms in ways that (often unintentionally) promote white supremacist language practices that are connected to other forms of social injustice such as nativism, xenophobia, classism, sexism, and heteronormativity. Thus, as we develop anti-racist writing pedagogies, we as teachers must turn a critical eye on the standards we were taught and uphold regularly in our own careers and classrooms.

For though we seek to support our students – to provide them with the tools and knowledge to succeed as writers in academia – by holding them to the standards of our disciplines and academic English, we must also consider how do so in ways that are consistent with our commitment to anti-racist pedagogy. Take Vershawn Young’s persuasive (and peer-reviewed!) response to Stanley Fish’s New York Times series about teaching writing. As Young makes clear, writing in your own language and dialect does not diminish your potential to be intelligent or successful in or outside of academia. For, as Young argues, complex argumentation, clarity of language, and depth of thought exist in all languages and dialects. We are merely trained (and disciplined) into thinking that academic writing must look a certain way.

Developing anti-racist writing pedagogies takes time, and the work is difficult. But it is work that this collective is dedicated to supporting. Below, we have included readings about anti-racism and social justice in the writing classroom (include a link that jumps them to that section) as well as practical ways to incorporate anti-racist writing pedagogies in your classrooms (include a link that jumps them to that section).

How can this happen?

Below are some examples of how anti-racism and social justice can become more central in your writing classroom:

Instruction, Activities, and Class Discussion

- Teach writing as a complex process rather than a polished product; one that will challenge students cognitively as much as it will emotionally; one that will make them question who they are and what they think and who needs to hear their ideas; one that can be beautiful and empowering and harmful and challenging–sometimes all at the same time.

- Centralize rhetorical situations and writing contexts rather than language standards in your writing classroom. Show how audience expectations shape the choices we make as writers; or, illustrate how different contexts require different writing. For example, create a powerpoint with writing from a variety of sources such as a tweet, the first paragraph of a news article, the conclusion of your favorite academic article, and an instagram caption from an art museum. Show students each piece of writing and see if they can guess where it was originally published. Students will end up debating language use, structure, content, and more. In doing so, they come to realize that writing is effective for different reasons based on the writing context rather than a singular standard.

- Illuminate that producing standard academic english is, ultimately, a choice. As Cox and Matsuda, et. al, explain, students can assimilate, accommodate, or separate from academic standards while still producing intelligent and groundbreaking work.

- Talk to your students about academic writing standards and language practices. We do not need to hide the fact that these standards can be used in ways that devalue other language practices and the people and communities they stem from. We may not all feel comfortable having your students submit writing that challenges or only partly adheres to academic standards, but any of us can open up a dialogue about writing and social justice. For example, have a class discussion about “good writing.” Ask your students to consider what parts of their definitions come from academic habitus — writing white versus writing well; producing logical arguments rather than basing claims on lived experience, etc.

Assignments

- Create opportunities for students to develop their sense of self and their values as thinkers, writers, and people. Usually, these assignments are ungraded but still earn points. This signals to students that writing can be a place of discovery and learning in addition to a mode of communicating.

- Create an assignment in which students can write to an audience that does not use standardized English.

- Have students find examples of successful pieces of writing that do not use standardized English. Have them research where these pieces of writing exist and have them explain what, to them, makes such writing successful.

- Have students research (through interviews with each other or a discourse analysis of past papers) how assessment and feedback on their writing has shaped their own ideas about what kind of language practices are valuable and transferrable into the workforce.

- Ask students to research how academics across the globe structure arguments. For example, what is considered ‘logical’ in Germany? in China? In France? Try writing a paper in a different academic standard.

- When designing research projects, allow students to engage with academic sources and with non-academic sources such as their families and communities and archives that have been overlooked or lost.

Feedback and Assessment

- When assessing writing, try to place more weight on ideas, use of evidence, and rhetorical thoughtfulness in the construction of the essay rather than language standards.

- Engage in the ways your students use language, rather than correcting their language practices.

- Allow your students to write as they wish, rather than require they produce standard academic English. This means making room for other Englishes and dialects like African American Vernacular English (AAVE) or translanguaging. Depending on who you are and what languages you use regularly, this will likely mean that you slow down or use a translation service.

- Have your students create their own writing standards. Debate all elements of writing that will be assessed. Ask them to think about the importance of grammar, organization, transitional sentences, evidence, and thesis statements.

- Decenter yourself and let your students evaluate each others’ writing. This helps them see how many different possibilities can exist for a singular prompt. This counters the idea that there is a singular ‘right’ way to write.

- Instead of correcting writing (which assumes that you know what your students are trying to say), point out your confusion and ask questions that illustrate how their syntax and sentence structure communications meaning. For example, instead of adding a comma because it is ‘correct’, take the time to explain why you think a comma is helpful for you as a reader. Similarly, if verb tense shifts throughout their essay, point it out and ask them why they think they made this shift in tense. They might be attempting to reconcile historical fact with present experience, which requires more than a simple correction.

- Try labor or contract grading, as detailed by Asao Inoue.

- Ask students to reflect on the judgements we make about what writing is ‘good’. Where do these judgements come from? How do these judgements relate to the white habitus of academia? There is no easy answer to these questions, but asking students to think about assessment critically is anti-racist work.

Research on Anti-Racism and Social Justice in the Writing Classroom

- Steven Alvarez’s piece in Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition Studies

- Catherine Prendergast’s Literacy and Racial Justice

- Laura Greenfield’s “The ‘Standard English’ Fairy Tale”

- Rosina Lippi-Green’s Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States

- Bruce Horner, Min-Zhan Lu, Jacqueline Jones Royster, and John Trimbur’s “Language difference in writing: toward a translingual approach”

- James Baldwin’s “If Black English isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?”

- Vershawn Ashanti Young’s “‘Nah, We Straight’: An Argument Against Code Switching”

- Performing Antiracist Pedagogy in Rhetoric, Writing, and Communication edited by Frankie Condon and Vershawn Ashanti Young

- Asao Inoue’s Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future

- Min-Zhan Lu’s “Professing Multiculturalism: The Politics of Style in the Contact Zone”

- Language Diversity in the Classroom: From Intention to Practice edited by Geneva Smitherman and Victor Villanueva with foreword by Suresh Canagarajah

- Special Issue: “Anti-Racist Activism: Teaching Rhetoric and Writing”

- Shane A. McCoy’s “Writing for Justice in First-Year Composition”

- Michele Fazio’s Teaching Note “Taking Action: Writing to End White Supremacy”

- Other People’s English: Code-Meshing, Code-Switching, and African American Literacy edited by Vershawn Ashanti Young, Rusty Barrett, Y’Shanda Young-Rivera, and Kim Brian Lovejoy

- Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education by Nelson Flores and Jonathan Rosa

Statements on Anti-Racism, Language Diversity, Social Justice, and Writing

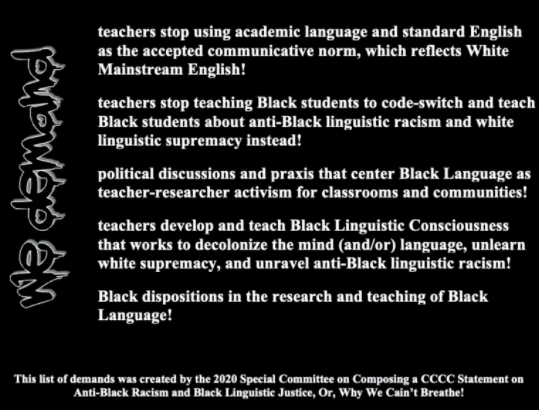

- CCCC’s 1974 statement student’s rights to their own language (reaffirmed in 2003 and 2014).

- IWCA’s Position Statement on Racism, Anti-Immigration, and Linguistic Intolerance (2010)

Talks on Anti-Racism and Language Diversity

Asao B. Inoue deliver’s the 2019 Conference on College Composition and Communication keynote address entitled “How Do We Language So People Stop Killing Each Other, Or What Do We Do About White Language Supremacy?”